Sufficiency Economy

Water Management and Village Development program

Page under Development

Water Management and Village Development Project (in Thai สร้างคลองสร้างคน meaning Build Klong, Build People Project) is one of our two flagship programs. Better water management is the first step in releasing productivity by adding water resource to the existing resources of land, villagers' labour, and villagers' agriculture know-how.

Embedded in the program is "Build People" which concentrates on Good Governance - the integration of morality and management principles. Further steps would be to introduce management techniques to assist villagers in their complete cycle of planting and marketing of their products.

And yet further, we can think about clusters of villages owning and operating their own rice mills and other factories, thereby integrating forward to manufacturing and sharing in that sector of the economy.

The water management challenge in Isaan

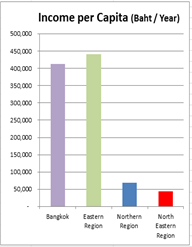

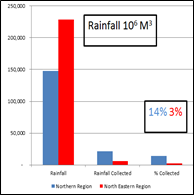

Northeast Thailand, or Isaan, is the poorest region in Thailand. Various estimates place its per capita GDP at just 10% to 14% of that in Greater Bangkok and the export-driven industrialized Eastern Seaboard areas. Isaan is usually described as “arid - very dry” - to explain low incomes from agriculture. Yet the Northeast receives 50% more rainfall each year than the identically-sized Northern region: 225 billion cubic metres on 171,000 sq. km. of area for the Northeast versus 145 billion cubic metres on the North’s 170,000 sq. km.

The North, however, manages to collect 14% of its rainfall, whereas the Northeast retains only 3%. In addition, there is high variability from year to year in the amount and timing of rainfall in the Northeast, resulting in wide swings in output per hectare.

The topography of northern Thailand is relatively hilly, whereas the Northeast is relatively flat. Water collection and storage strategies need to be suitable for the flat Northeast

The topography of northern Thailand is relatively hilly, whereas the Northeast is relatively flat. Water collection and storage strategies need to be suitable for the flat Northeast

Region.

Projects to collect and distribute water in the Northeast need to be localized at the village level. The large dams and irrigation programs suitable for the North will not work in the Northeast. The centralized planning of large water management projects can not address the localized water needs of the Northeast.

In sum, farm incomes in the Northeast can rise with better water management - having the right amount of water, in the right place, at the right time for the farmers. EPWF facilitates programs at the village level to define local water management projects and make them concrete in documentary form which can be submitted for consideration for funding by both the private sector and public sector.

stoppage during rainy season. Comments from villagers: “If we

did not have the water from the klong, all the crop will die.

Now feel very good we have water conveniently using two pumps.” “If we do not have water, how can we eat and survive. Now with water from the klong, we have good rice crop, bananas, vegetables, sugar cane.”

Better water management and village development ... and why is it important?

EPWF initiated the Water Management and Village Development Project (in Thai โครงการสร้างคลองสร้างคน meaning Build Klong, Build People Project) as a way of starting to address the wide income gap between the Northeast region and the Bangkok-Eastern Seaboard area.

Various sources have estimated that the Northeast has from one seventh to as little as one tenth of the per capita income of Bangkok and the Eastern Seaboard. If economic inequality of this magnitude is not the reason, it is certainly a major contributor to the social divide and political divide confronting Thailand in recent years.

Later, it was found that Good Governance is also an over-riding issue and the key factor for EPWF’s continued promotion of this program and solicitation for sponsorship. This is illustrated in the poster for the project below with the slogan in Thai: “Honesty Industrious Thrifty Sacrifice Gratefulness”. EPWF embed Good Governance in the implementation of the Water Management and Village Development Projects.

morality and management principles.

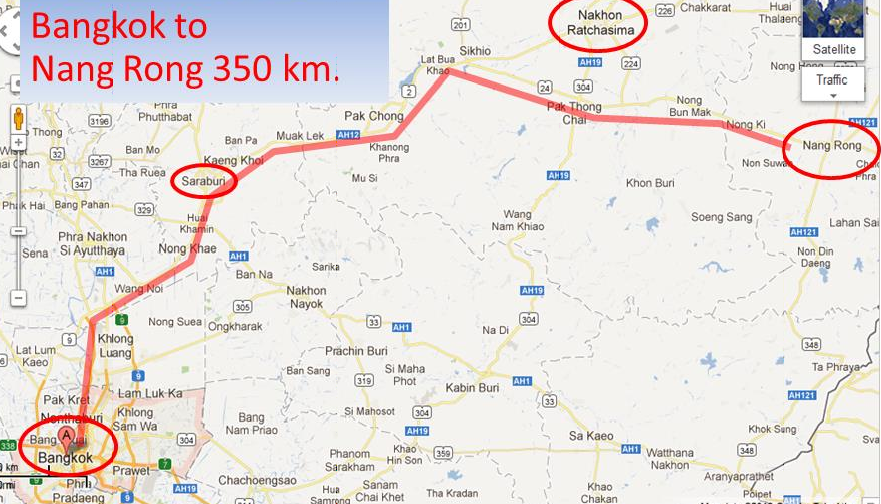

Amphoe Nangrong, Buriram Province, about 350 km

from Bangkok and expands into other tambols in

Amphoe Nangrong.

2011-2012 Nongtakian klong project and 2013 klong extension to Chockchai

The Nongtakian Klong Project provides an illustration of what can be accomplished when villagers take a constructionist view in defining a problem and finding a solution to it.

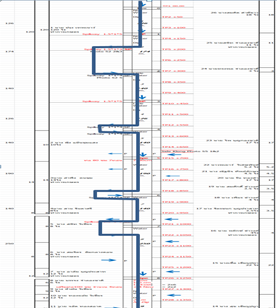

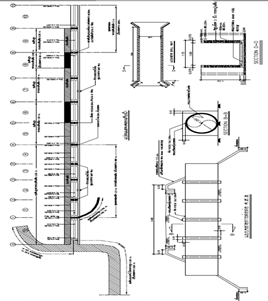

There was sufficient water from the Lamart River and Pohdaeng Weir for all the farmers in the area, but it was in the wrong place for a group of about 15 landowners whose fields were one to 2 km. distant from either the existing klong or the river. The solution villagers came up with was to construct a new klong of sufficient depth (about 3.4 m.) about 2 km. in length (later extended to 2.7 km.) which would draw water from the existing klong, the river and the weir and transport water by gravity flow to higher ground.

In the process, nine storage ponds (not shown on this map) were also constructed, partly to capture any overflow from irrigation, but particularly to collect floodwater during the rainy season.

As long as there is water at the Pohdaeng Weir, unlimited water is available to Nongtakian villagers along the first 2 km. of the klong, and with the klong extension along a further 0.7 km . to Chokchai villagers, and thereby also extending the project into the next Tambol Lamsaiyong.

hold water for Nongtakian Klong.

deep to transport water by

gravitational flow to higher ground

Vetiver grass planted to retain the

earthen side of the klong.

2012 - 2013 Projects at Thaithong and Nongthonglim

Besides the extension of the Nongtakian Klong to Chockchai reported in the preceding paragraph, EPWF implemented two projects in 2012 - 2013.

Thaithong : The second project was a concrete water channel of 150 m. which took flood waters potentially damaging 50 rai of tapioca fields costing crop loss of Baht 500,000 per year and perennial flooding of Thaithong villagers’ homes.

Nongthonglim Klong: The third project was the deepening along 750 m. of a an existing klong of 1,450 m. and the upgrading of the whole irrigation system by the building and repairing of retention dams, spillway and pipe systems to hold water and irrigate the surrounding fields according to agricultural requirements using energy saving gravitational flow. The earth from the excavated earth was used to upgrade the road along the whole 1,450 m. klong as well as 1,000 m. of an approach road to the klong. In total, 400 rai of land on either side of the klong with rice crop valued at 1.3 million per year will be serviced by the Nongthonglim klong; in addition klong water can be used for vegetable farming to further increase agricultural production during the dry season.

road.

cover for safety and adding to width of road.

klong repaired using earth from excavated klong. Village

head of Nongthonglim in picture.

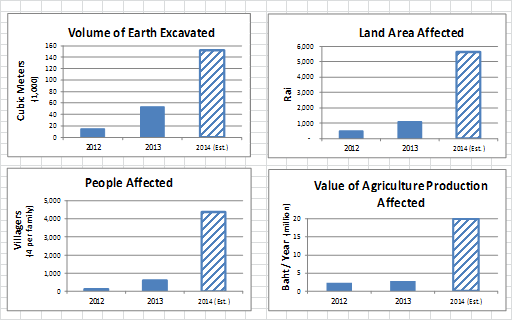

2013 - 2014 New Projects in planning and implementation phase

Expansion into the new tambol of Lamsaiyong in 2013 has yielded two new projects.

Lamsaiyong: The first is the Lamsaiyong klong which will complete the missing 2,400 m. section of an exisiting klong. The significance of this project is that will connect to an existing system of small feeder channels which together with the 2,400 m. of klong to be excavated will service a wide area of 3,500 rai affecting 470 households from 5 villages with a rice crop valued at Baht 17 million per year, not counting vegetable farming during the dry season.

Furthermore, the excavated earth will be used to construct two roads on either side of the new klong where there is presently none. This will greatly increase the productivity of villagers by providing access to fields for cultivation and transportation of crops.

missing section of klong and provide water to small

feeder channels to cover a large area of farm land.

The earth from the klong will be used to make road on

both sides of the excavated klong to provide road access

to fields: presently there is none. This will increase

productivity of villagers

Lamsaiyong klong.

Nongyang: The second project at Tambol Lamsaiyong is the ponds upgrade at Nongyang village with the prime aim of providing household water to 440 households in 3 villages which are now subject to water rationing. The water is also used for the water purification plant for drinking water, and as a last priority if available for vegetable farming in small garden plots in the village.

and water for purification for drinking. Existing water

tower and pumping station shown at top of picture.

water.

Nongthonglim Concrete Channel: The third project is the extension of the concrete water channel at Thaithong completed in 2013. The water from Thaithong village flows to Nongthonglim village before emptying into a pond in Limthong village. The unblocking of the water channel at Thaithong has resulted in a flood of water at Nongthonglim threatening the existing road and some 50 households. The 150 m. concrete channel from Thaithong will be extended 280 m. along the Nongthonglim sector. The water finally collected at the existing Limthong pond will be used for agricultural purposes.

to direct flood waters to existing pond in Limthong

village.

to concrete water channel for faster flow during heavy rain

to prevent flooding and damage to existing concrete road.

Nongmuang: The fourth project is a new 250 m. klong at Nongmuang which will source water from an existing reservoir of 200 rai to the rice fields next to the klong and in addition feed another 250 m. of small feeder channels to be upgraded. The total system will service a wide area of 600 rai affecting 150 households from 4 villages and with rice crop valued at Baht 3 million, not counting vegetable farming during the dry season.

Also of significance is the location of the project in another tambol to mark a further geographic expansion of the program.

existing reservoir of 200 rai (bottom right of page) and

connect with two water feeder channels (blue).

raise the level of the water in the reservoir to provide more water for the klong. The klong will be deepened.

Good governance and EPWF’s partnership with the Private Sector

Good governance is the integration of morality with sound management principles. We seek to promote good governance in the implementation of the village programs and seek to promote this concept with the private sector, notably companies who participate in the Private Sector Collective Action Against Corruption movement and the Anti-corruption Organization of Thailand, not only to support our program but to develop other programs to promote good governance.

We are most appreciative for the support we have received from Thai Oil Public Company Limited, a member of the PTT Group, for their generous financial support as well as the time of their management and engineering staff to give advice on the project and training to villagers and EPWF officers. Thaioil is a signatory company of Thailand's Private Sector Collective Action Coalition Against Corruption's Declaration of Intent.

EPWF makes it clear to villagers with viable projects that the projects must be transparent as this was the basis on which EPWF solicits funds from the private sector CSR to support the village. As custodians of our donors’ funds, we walk through every stage of the governance of a project with the villagers.

We begin with a clear project definition based on sound engineering and business principles; we continue with oversight of a competitive bidding process; and we follow through with project implementation and handover. We anticipate that these examples of good governance will be mentioned favorably at the monthly tambol and amphoe level meetings attended by all villages. It is our hope that other villagers will in their turn choose the alternative of good governance which can then be rewarded by private sector support.

at a crossroads. We have a

task ahead of us - to rebuild the country's governance."

Mr. Anand Panyarachun Chairman of the Board, The Siam Commercial Bank PCL.

has to do with integrating morality and management principles. If a society has

good morality and

management principles, it

is a developed society.

Mr. Krirk-Krai Jirapaet

Chairman of Thai Institute

of Directors (IOD)

villagers in management and implementation of projects:

from conceptual drawing

clear project specification, accurate budget estimate,

transparent bidding, and finally control of project execution.

terms of technical training, management,

and accounting.

Local Development Officers in way to measure elevation and calculate elevation readings

EPWF’s long history in water related issues

Water has been a concern of EPWF from its beginning. One of the projects approved by the board at its second annu al meeting in October 1969 was proposed by Founding Director M.R. Seni Pramote and involved the digging of 10 water wells in the northeast at a cost of 500,000 Baht. Similar small projects followed over the years.

EPWF returned to work in the villages in Amphoe Nangrong Buriram Province in 1999 and our experience, both with Suksapattana and EPWF shows that a constructionist learning approach can be successful with villagers. It is a highly productive way for villagers to approach their problems and devise possible solutions as individuals and also at the level of the village. Importantly, the constructionist approach of setting ideas and plans on paper promotes clear project definition and transparent budgeting for projects, in other words good governance.

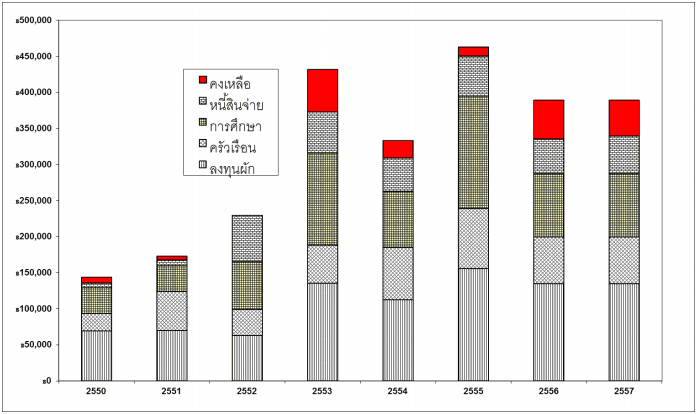

In one prime example, the villager is able to summarize his economic activity in the past and his future plans with management planning tools and the use of computer technology. He was able to greatly increase his income by good planning and hard work whicCash flow reflecting actual results for four years and projections for 2 years. Na Mao is a rice farmer who supplemented his income by casual labour. After he had access to water year round and used management planning tools, he was able to plan and record his income and costs.h enabled him to provide for his family and the education needs of his children up to university level.

is a prime example of villager

who has taken on board

From bottom to top, the bar charts show 1) cost of production, 2) daily household costs, 3) education costs (elder daughter supported through university education in agriculture, 4) debt servicing, and 5) surplus funds in red used for re-investment. Increase in assets is not shown on the chart. Right hand axis is Baht.

The way ahead ...

EPWF believes that the model it has developed has enormous potential for bettering the lives of Thais in all parts of the country. Apart from the underlying and pervasive importance of elimination corruption and promoting good governance, we think the way ahead has one major challenge and one major opportunity.

The way ahead ... the challenge of local development officers (LDOs)

Local development officers are a key aspect of the program. At this early stage, it may be too much to ask villagers as individuals and as a village group to learn and practice all the management skills and to develop computer literacy. In the case of water resources management, engineering skills are also transferred from partner organizations such as Thai Oil Public Company Limited. LDOs learn at the same time as the villagers but they usually learn faster and retain more with more time dedicated to development work. When the facilitator leaves, the LDOs help the villagers consolidate their learning.

the solving of problems with group participation.

The challenge is recruiting, training and retaining competent LDOs to work with the villagers. The scarcity of suitable personnel reflects the poor state of rural education which, of course, is one of the root causes for low incomes and scant opportunities in the Northeast. Apart from considerable skills in constructionist learning, LDOs also need advanced skills in human relations in a Thai social setting. It is not easy for an LDO in his or her 20s or 30s to facilitate a villager in his 40s or 50s with 20 years of farming and village management experience .

EPWF had employed numerous local development officers on full-time and part-time basis; the challenge remains finding and retaining staff. Presently we have one full-time staff supported by two part-time locally and one part-time staff from Bangkok. Mr. Bangkok Chowkwanyun, EPWF General Manager and Director, spends about one-quarter of his time on this flagship program. Supporting this core team and increasing it on a long term basis are the essential factors in the expansion of this program. The key is to support and promote a cascading growth of local development officers facilitating other local development officers.

The way ahead ... the opportunity of information and communications technology

The incredible growth and wide-spread popularity of handheld computer devices, such as ‘smart phones’ and tablets, along with the obvious power of social networking over the Internet, suggest there may be an enormous opportunity to leverage the financial and human resources available from EPWF and its private sector partners. Information and communications technology is key, not only in the application of constructionism, but potentially in establishing effective direct communication among villagers and between villagers and donors.

It is not too difficult to imagine a world in which villagers are connected in real time over social networks with other villagers, sharing knowledge of production and marketing problems and solutions developed through constructionist learning. Marketing through social networking seems to have great potential, especially if organic agriculture methods are adopted.

Indeed, one can even imagine direct contact between villagers in Northeast Thailand and ‘compassionate givers’ in Bangkok and even spread throughout the world. At some point perhaps the village or even individual villagers could begin to function as a micro-or nano-non-profit organization dealing directly with donors. Eventually villagers could take the responsible for obtaining a large portion of the funding required for their projects. But the underlying message always is that corruption must be eliminated for this bright future to materialize.

Links such as these will soon narrow the gaps among people, both in understanding and empathy as well as in material and spiritual wellbeing.

Water: An EPWF concern from the start - the historic background

The beginning phase

The interim phase

Water has been a concern of EPWF from its beginning. One of the projects approved by the board at its second annual meeting in October 1969 was proposed by Founding Director M.R. Seni Pramote and involved the digging of 10 water wells in the northeast at a cost of 500,000 Baht. Similar small projects followed over the years.

EPWF again became directly involved in village development from 1999 to 2003 through the participation of Mr. Bangkok Chowkwanyun, EPWF General Manager and Director, in theLighthouse Project of Suksapattana Foundation in Amphoe Nangrong Buriram Province, which used a constructionist approach.

The project team started work with Population and Community Development Association (PDA) headed by Mr. Meechai Viravaidya and later moved to be resident in Limthong village.

During these years, EPWF was able to understand the villagers’ needs for better management including accounting skills to control his farming “business” and debt management. Another learning point was the inadequacy of government funding for rural infrastructure investment and weak infrastructure project planning. This laid the ground work for what was to follow.

From 2001 to 2006, EPWF also worked on the education side of Lighthouse Project while keeping up with the Village Development Project and in touch with PDA in Nangrong. In 2002 and 2006, EPWF made two donations of 500,000 baht and 240,000 baht respectively through PDA for household water development projects.

From 2009, HAII carried on the program at Limthong and the three associated villages. In 2010, EPWF returned to the Limthong project with HAII to work on the management and good governance aspects. EPWF also continued the education program pioneered earlier. It was found that education teaching is in a very sorry state but constructionist teaching methods in a tutoring style on weekends had a great and ready impact on the students; the problem was continuity of both students and facilitators but even the very limited intervention can be worthwhile leading to at least two students attending university studying engineering and computer science where this would be deemed out of their consideration in the past.

In 2006, EPWF learned that the villagers at Limthong had a project combining with three other villages to make a large klong in association with Dr. Royol Chitradon of the Hydro and Agro Informatics Institute (HAII), Ministry of Science and Technology. EPWF recognized the opportunity to embed a villager management development program to blossom alongside the agriculture opportunities opened up by the new klong and made an investment of Baht 2.4 million in 2007 and 2008 for the training of local development officers as facilitators of the villagers and working capital for villagers to start their agriculture projects with the arrival of the klong. During these two years, EPWF learned about water management in the Northeast’s particular topography. At the same time, EPWF started to pioneer children’s education program in the village using the experience garnered at Project Lighthouse.

notebooks and share their learning.

on paper onto white board for clear and efficient discussion

and transparent participatory discussion and decision making.

discussed with estimated budget requirments.

The expansion phase as a flagship program

From 2011, EPWF armed with management skills and a basic understanding of water resources assumed responsibility for both managerial and financial inputs, thereby making it one of our two flagship projects, and branched out in search of other development areas. By the end of 2013, EPWF had invested 5.5 million baht in water and village development program.

officers continue to facilitate

management skills of individual village family level.

The Water Management and Village Development program is based on several interrelated premises and assumptions.

Agriculture: A viable option in the Northeast

Covering the “last mile”

Grass roots approach

... by villagers ... for villagers

Agriculture, as opposed to manufacturing or services, will continue to be the core economic activity in the Northeast for the foreseeable future.

Agriculture in the Northeast can be made much more productive with better management of existing water resources. In spite of difficult topography and poor soil, a moderately productive agriculture is possible with applications of water in the right amounts at the right times over the growing cycle. The problem is not insufficient water; the problem is insufficient water management.

The way to increase incomes in the Northeast is by firstly raising productivity of existing crops and second by diversifying into higher value-added agriculture. Both are possible with better water management at the village and the farm level.

The information and communications technology (ICT) industry talks about the ‘last mile’ problem, or the difficulty of connecting the household or small business end user to the optical cable ‘backbone’ of the high speed digital network.

Water management in the Northeast has exactly the same problem. Water is often or even usually available within a few hundred meters of a villager’s field, but there is no way to move it to where it is required. In its water management activities, EPWF has focused on this ‘last mile’ problem. In some cases it is merely a matter of repairing or upgrading existing irrigation infrastructure. In other cases it may be necessary to dig a new canal. The constructionist learning method (see below) allows the villagers themselves to define the problem and to propose solutions, usually with assistance from the facilitator and technical inputs from our private sector partners.

EPWF believes - and has found to be true - that the villagers themselves are the best judges of what projects they need to improve their lives. This rural development program, therefore, is about people taking the initiative at a grass root level and learning. The curriculum is their planning, financing - with emphasis on the private sector - and implementing projects to improve their economic condition - initially with the help of EPWF and our partners. Using a constructionist approach to learning, villagers can define their problems and analyse solutions at the grass roots level in a transparent manner.

Constructionism for water management and village program

EPWF has worked in the villages since 1999 and our experience, both with Suksapattana and EPWF shows that a constructionist learning approach can be successful with villagers. It is a highly productive way for villagers to approach their problems and devise possible solutions.

One of the basic principles of constructionism is that projects must be able to be shared among learners and between learners and facilitators. Projects must be in a form that others can see and learn from. A further prerequisite is that the learners must have sufficient basic skills - primarily arithmetic - to enable them to work meaningfully on projects. EPWF has had to devise methods and techniques to meet both of these challenges in its Water Development and Village Development program. A powerful constructionist technique is a step by step approach ("the next step") starting from some skill or knowledge which the villager can master and moving in small manageable learning steps to reach the required skills and knowledge.

Graphs were introduced, first manually and then computer generated.

These steps enabled the villager to plan higher productivity agriculture in a holistic manner in accordance to the sufficiency economy farming concept expounded by His Majesty the King. Multi-cropping enabled the villagers to diversify the price and volume risks of agriculture products and to attain a higher level of sufficiency economy.

The possibility of encouraging villagers’ children to use their arithmetic and computer skills (through one tablet, one child), supplemented by basic accounting skills, to help their parents and the village community is also an option we are exploring.

Two areas need further development by villagers and EPWF. Firstly, visits were made to other farms to learn about new crops and farming techniques. More has to be learned. Secondly, marketing has to be addressed, including the possibility of higher value products in terms of crops and also in terms of less use of chemical pesticides and fertilizers for the health of consumers as well as the villagers.

But... Elimination of village corruption is essential

There are numerous divisions in our nation at present. But perhaps the most pervasive is the one between good governance - transparency and honesty - and its opposite - lack of transparency and corruption.

Nearly 15 years of experience working in villages has shown, perhaps not surprisingly, that Thailand’s national disease of graft and corruption extends to the village level. The water management projects will work only if honest and upright village leaders manage the projects for the benefit of the many rather than for a few “leaders.” Honesty is an absolute necessity if villages and villagers are to attract direct support from the public.

Accordingly, the constructionist approach has moved beyond good project planning and budgeting to transparency for good governance. The original goal of the program for better economic and social conditions remains, but has expanded to include reduction of the national malaise of corruption by the people themselves working at the grass roots level.

The crux is finding the honest and upright village leaders to be examples for other villagers to demand good governance in their villages.

The private sector must be involved

No matter how well-funded or well-intentioned, the evidence is that large-scale government water management programs are not going to solve the Northeast villagers’ real problems. It is very difficult for an official in Bangkok to see and understand what the “last mile” really means on the ground in Nangrong.

Furthermore, “last mile” projects are usually relatively small, perhaps 0.5 to 1.0 million baht each. They seem insignificant when billions of baht are involved in a large scale, showpiece project. Even when funds have been allocated for village projects, the funds may not trickle down through many layers of bureaucracy to the tambol level where they are needed.

Accordingly, “last mile” water projects are ideally suited to the CSR (corporate social responsibility) activities of companies in terms of reasonable size but high impact. Apart from funding, companies are often in a position to provide essential technical assistance to the EPWF facilitators and to the village learners.

For example, in late 2012 Thai Oil Public Company Limited led in becoming the first major corporation to support a “last mile” project in Nangrong, Buriram which will be completed in 2013. Thai Oil and EPWF together developed a “three-person learning model” which emphasizes that professional civil engineers work together with the community leaders and with dedicated local learners in designing and executing successful projects.

for the use of projects in Village Development Project.

A village has data ...

but does not turn data into information

From memory... to paper... to bytes...

From data... to information... to wisdom

To an outsider one of the most striking features of village life is that there is hardly any use at all of record keeping or documentation - everything is ‘in the head’. Even basic information such as the profitability of a crop is unknown, although the data on individual price and cost items are burned in the memory. As a result there is little planning and life is very much on a day to day basis.

Not using paper or its equivalent is obviously a serious limitation for good decision making. It is very difficult to compare in one’s head the relative profitability of three or even two crops over a growing cycle. ‘What if’ scenarios are nearly impossible to imagine without some sort of visual representation of alternative paths and outcomes.

Thus the first step was to encourage and assist villagers to take the conceptual leap of moving from a paper-less society to a paper-full one. Paper records allow the use of simple management concepts for project planning, cash flow and accounting, adapted to the requirements of the villagers. Basic management tools, such as a white board and projectors, are also introduced for sharing information and decision making. Accounting is needed for transparency. Finally, computer technology is used to increase productivity by making tedious manual planning computer efficient and practical. This initial work was funded by Suksapattana Foundation with Khun Bangkok Chowkwanyun as the facilitator. The Suksapattana Foundation was in turn initiated by EPWF.

EPWF Director and General

Manager planning with villagers in

Nang Rong, Buriram in 2012